Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

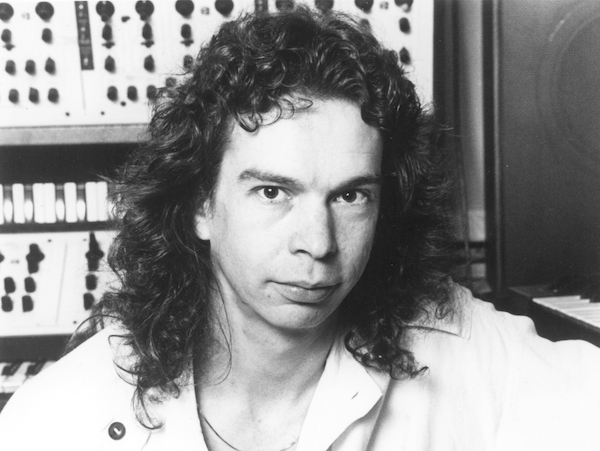

Lyle Mays (1953– 2020)

(Photo: Joji Sawa/Geffen/DownBeat Archives)Lyle Mays, the keyboardist who spent a significant portion of his career recording and performing as a member of the Pat Metheny Group, died Feb. 10 at Adventist Hospital in Simi Valley, California. He was 66.

While the specific cause of death was not made public by press time, Mays’ niece, jazz vocalist Aubrey Johnson, said in a social media post that it came “after a long battle with a recurring illness.”

“Lyle was a brilliant musician and person, and a genius in every sense of the word,” she wrote. “He was my dear uncle, mentor, and friend and words cannot express the depth of my grief.”

After the news of Mays’ death was reported during the second full week of February, Metheny had the following message posted to his website: “Lyle was one of the greatest musicians I have ever known. Across more than 30 years, every moment we shared in music was special. From the first notes we played together, we had an immediate bond. His broad intelligence and musical wisdom informed every aspect of who he was in every way. I will miss him with all my heart.”

Mays was born in Wausaukee, Wisconsin, on Nov. 27, 1953, to a musical family. While his parents held steady day jobs, both harbored a deep love of music and played instruments: His father was a self-taught guitarist, and his mother played piano and organ, mostly in church. Mays followed suit, taking piano lessons from a local teacher, and eventually began playing organ in his hometown church as a teen.

Around the same time, he became an ardent jazz fan after coming across Bill Evans’ At The Montreux Jazz Festival, a live trio album on the Verve imprint that featured bassist Eddie Gomez and drummer Jack DeJohnette. According to Steven Cantor, the co-producer of Mays’ first two solo albums (a 1986 self-titled LP and 1988’s Street Dreams), “He was completely mystified by [the live Evans recording]. He couldn’t understand it at all. But given his interest in music and that he was playing piano at the time, it became something that he had to figure out.”

Mays’ jazz studies landed him at North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas), where he studied under the direction of Leon Breeden and joined the school’s prestigious One O’Clock Lab Band, alongside bassist and future collaborator Marc Johnson and future Freddie Hubbard drummer Steve Houghton. Mays became the group’s chief arranger, with his distinctive touch and impressionistic piano solos heard on the band’s Grammy-nominated album, Lab ’75!

While Mays’ first professional gig out of college was playing with Woody Herman’s band, it was his work with Metheny that defined the next 30 years of his career. The two first met at a jazz festival in Wichita, Kansas, during 1974. But it would be several years before they regularly began performing and recording together, starting with Metheny’s 1977 album Watercolors. From there, Mays became the longest tenured member of the Pat Metheny Group, co-writing much of the band’s material and blending acoustic piano with an ever-growing array of synthesizers to add misty textures and whimsy to their sessions.

Mays and Metheny’s creative partnership extended outside the band, as well. 1981 saw the release of their duo album, As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls, and Metheny had a hand in producing some recordings where Mays took top billing: 1993’s Fictionary (with bassist Johnson and drummer DeJohnette) and 2000’s Solo (Improvisations For Extended Piano). Some insight into what made their relationship so fruitful can be found in an interview Mays gave to DownBeat for the March 1993 edition, around the time Fictionary was released.

“We had just finished a tour, when Pat approached me and said, ‘You should go into the studio. I really think your playing is the best I’ve heard you play,’” Mays told writer Martin Johnson. “I was like ... thanks [shrugs]. I was almost resistant to the idea, though. I hadn’t prepared a record.

“On the first two records I did [Lyle Mays and Street Dreams], I spent a lot of time in preproduction orchestrating things. It wasn’t even on my mind to do an acoustic record. I have to give Pat credit; he kind of talked me into doing it.”

Another outlet for Mays came via commissions from Rabbit Ears, a production house that hired famous actors to read children’s stories and modern musicians to provide the soundtracks. Mays created two works for the company that allowed him to tap into his long-simmering classical influences.

“If you listen to the score for The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher,” said Cantor, who produced the sessions, “it’s Stravinsky. It’s L’histoire Du Soldat instrumentation. A six- or seven-piece ensemble with lots of woodwinds. And the other one he did, East of the Sun, West of the Moon, it was cinematic. He wrote a half hour of music that was so beautiful and so expansive and worked so well with the story.”

Following the release of the final Pat Metheny Group album, 2005’s This Way Up, Mays began his slow retreat from the music world.

As Metheny put it on his Facebook page recently, the grind of touring that was expected of any working jazz musician wore on Mays.

“The lifestyle of going out on the road night after night,” Metheny wrote, “for sometimes hundreds of nights at a time, is not for everyone and has real challenges ... . We did a brief round of gigs a while back, and it was clear in every way that he had had enough of hotels, buses, and so forth.”

Mays quietly lived out the rest of his days in California, working in the computer industry and encouraging the creative efforts of his niece. But what the world lost with his passing is, as Cantor put it, “an amazing intellect. Amazing focus and amazing clarity. And great art.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…